The ability for users to alter their transactions while they are still waiting for confirmation has considerably better the UX of using Bitcoin, as it allows users to unstuck transactions that would otherwise have taken weeks to process because of too small fees, or even to “cancel” a transaction they made by mistake.

Today’s mechanism for doing so, called Opt-in RBF, relies on the user’s transaction signaling that it can be replaced. While it has the great advantage of making it clear for any observer wether a transaction can potentially be replaced or not, it has some downsides, notably for protocols built on top of Bitcoin that rely on multiparty transactions, where multiple users take part in the construction and signing of a transaction by each contributing one or more input. This notably includes the Lightning Network, coinjoins and DLCs.

The attacks allowed by Opt-in RBF are, as of today, completely manageable. But they might cause substancial harm in the future, in terms of time and money for their victims. Hence the work led by Antoine Riard on an alternative replacing policy, which was merged a few days ago into Bitcoin Core, and which we cover in this article.

Current RBF policy

The current1 Replace-by-Fee policy is defined in BIP125, and details the rules under which an unconfimed transaction can be replaced in the mempools by a different version of itself. The BIP’s standard in itself is quite easy to read, but here is a summary:

- a transaction can signal to everyone that it can be replaced by having a nSequence strictly below 0xffffffff - 12

- if at least one input of a transaction signals that it can be replaced, then nodes should replace the original transaction with the new one in their mempool, provided that the new transaction follows a few rules:

- the new transaction must pay at least as much fees as the original transaction,

- the new transaction must also pay an additionnal fee for its own bandwith. For example, if the minimum relay fee3 globally is of 1 satoshi/vByte and the new transaction weights 500 vBytes, then the new transaction’s fees must be at least 500 sats higher than the original one. This is a protection against DoS attacks as, if it wasn’t the case, an attacker could easily spam the network with replacement transactions at no additionnal cost,

- some other rules irrelevant to this article.

This transaction replacing mechanism is remarkably balanced between all users and use cases. Indeed, some users might rely on the pseudo-finality of unconfirmed transactions, for example a merchant who wants to accept 0-confirmation Bitcoin payments so than customers don’t have to wait in line at the cashdesk for their transactions to confirm. Other users might be in dire need of the ability of replacing unconfirmed transactions, either because of a sustained high-fees environment like we experienced in 2017, or because the protocol they’re using works better with it. BIP125 plays the two sides of the fence: a merchant relying on 0-conf transactions can accept only transactions that don’t signal replacement (or have a different policy for big and small amounts), while users who need the replacement capability can enable it in their transactions. Ultimately, a new possibility was added to Bitcoin, and when “conflicts” arise, for example between a customer who wants to use RBF and a merchant who doesn’t want to recevie RBF-enabled transactions, they can be solved locally through bargain.

So, if BIP125’s Opt-in Replace-by-Fee is so great, why was a new mechanism merged into Bitcoin Core recently? Well, first, this mechanism is rather complementary than “new”. Second, BIP125’s policy, while great at the moment, could have introduced some actively exploitable attack vectors on protocols built on top of Bitcoin, such as Lightning, Coinjoins or DLCs.

A RBF Attack Vector

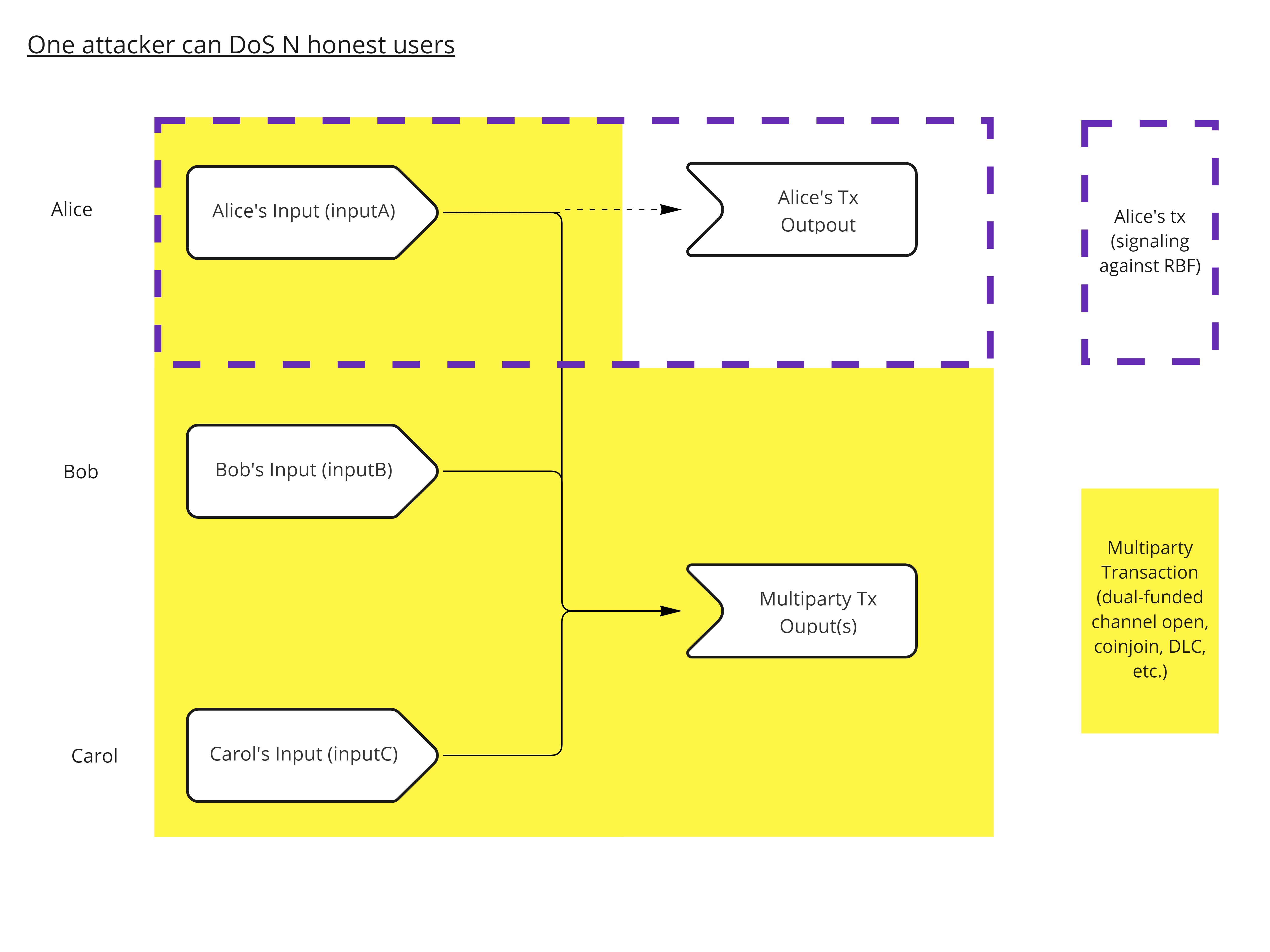

The following attack example was formulated by Antoine Riard, and is actionnable whenever a transaction is comprised of inputs from more than one party. This includes, for example, dual-funded Lightning channels (2 parties), DLCs (typically 2 parties) or coinjoins (N parties).

Here is a short description of the attack by Riard himself, as featured on the GitHub pull request:

There is a malicious exploitation where a participant to a multi-party transaction does not signal RBF for a double-spend of the contributed input. If this double-spend is propagated before the honest multi-party transactions that one will stuck in the issuer mempool. From then, the honest participant are left with two options, double-spend their own contributed inputs after a protocol timeout, and thus loosing the utility of their coins during this delay OR fee-bump the multi-party transaction as from their view of the network they might attribute the lack of confirmation to a low-grade feerate. This second reaction might be even worst in term of damages than the first one, as the malicious participant might replace its own double-spend to “unlock” the propagation of the fee-bumped-at-max multi-party transaction, far above the recent blocks feerate. Indeed, the fee-bumping strategies are certainly known by the attacker for open source software.

In a mail on the Lightning-dev mailing list, Riard also gave an example with 3 parties (Alice, Bob and Carol), which make the attack easier to understand.

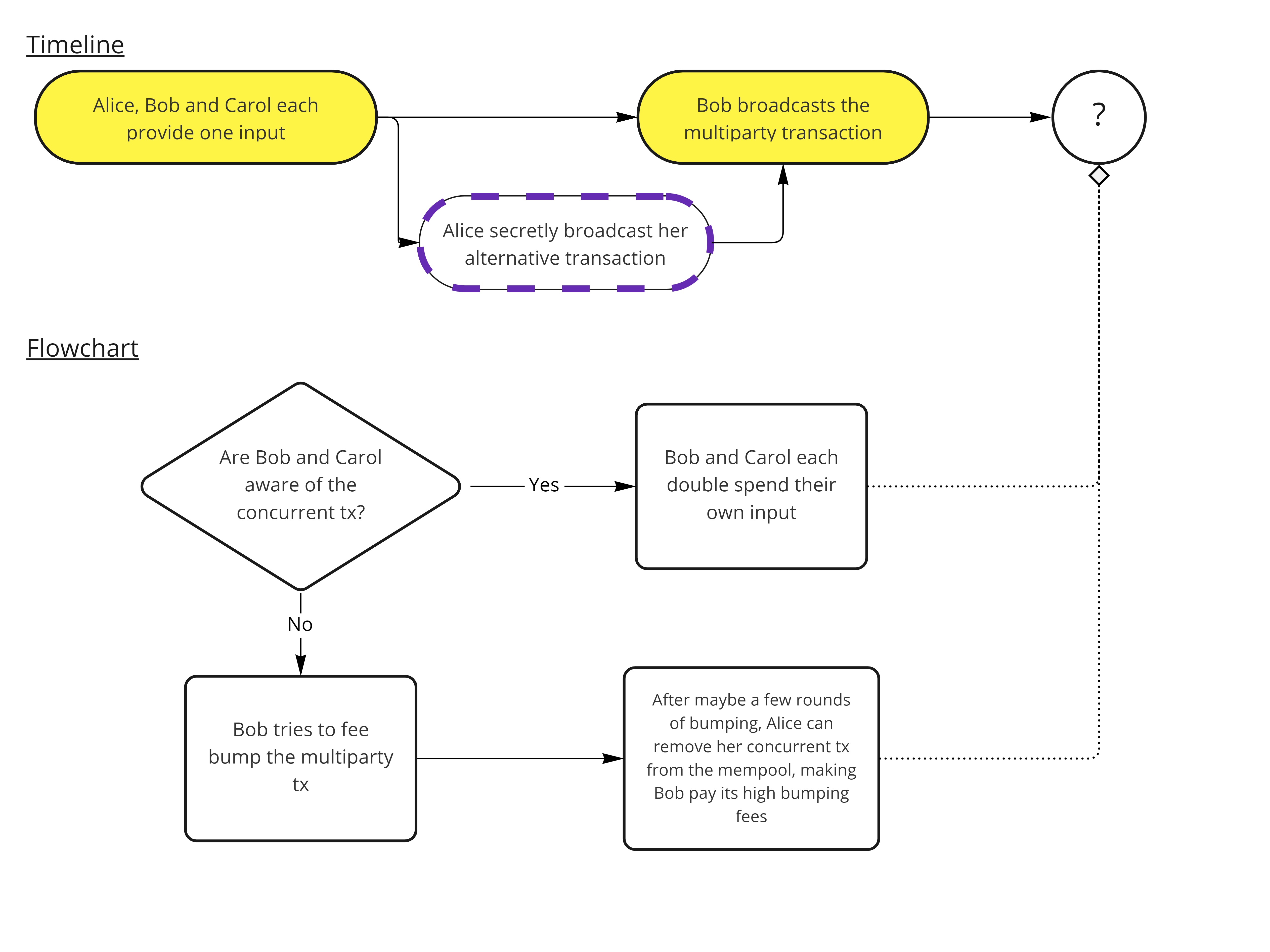

Imagine Alice, Bob and Carol take part in a common, multiparty transaction, where each one of them contributes one input. Each partipant provides its input along with a valid signature, the other two check the validity of the input, and one of them, say Bob, is responsible with sending the final transaction and, if need be, bump the transaction’s fees later on.

Alice could secretly prepare another conflicting transaction spending her own input, and which explicitely signals agaisnt replacement by having the nSequence of the input set to 0xffffffff. Then, if Alice connects directly to a vast number of nodes in the network and broadcast to them her own transaction, without telling Bob and Carol, just before Bob broadcasts the multiparty transaction, it would result in the multiparty transaction not being relayed, as it tries to spend the same input as a transaction that was seen before by most nodes, and which signals against replacement. Indeed, it would go against the “if at least one input of a transaction signals that it can be replaced” rule of Opt-in RBF, as the only input of the conflicting transaction clearly signals against replacement.

Alice secretly crafts her own conflicting transaction with the same input that she used in the multiparty transaction, and actively signals against replacement.

From then on, Bob and Carol have only two solutions:

- Double-spend their own input of the multiparty transaction, losing money (in additional fees) and time (notably if they have to wait for the expiration of a timeout, present in many protocols that rely on multiparty transactions).

- Try to fee-bump the multiparty transaction using Child-Pays-For-Parent (CPFP). This might lead to even more loss in money and time, as malicious Alice could remove her conflicting transaction from the mempool by replacing an unconfirmed parent (thus not breaking the rules of BIP125) after one or several fee-bumps occured. Once the conflicting transaction is evicted from the mempool, the multiparty one is relayed as normal, and will finally be mined with a maliciously inflated fee, potentially much higher than what would have been needed.

Alice prevents the multiparty transaction’s propagation by directly pushing her conflicting transaction first to a vast subset of the network.

As of today, this attack might seem to be a bit science-fiction. But in a world where services are in open competition with one another, it could leveraged as a weapon against one’s competitors. A Lightning Service Provided (LSP) could DoS its competitors with this attack, costing them time and money. Same goes, as far as I understand, for a coinjoin coordinator that would allow RBF-enabled transactions in its rounds. It must also be noted that this attack is particularly effective due to the asymmetry between the attacker and its victims: one attacker can cost-effectively DoS any arbitrary number of users.

The Fix

It is precisely to prevent this kinds of attacks that Antoine Riard proposed a modification to the way Bitcoin Core handles unconfirmed transactions replacement.

What’s new

The change introduces a new configuration option in Bitcoin Core, called mempoolfullrbf. If this option is set to true, the node will allow replacement even if the transaction doesn’t signal with an appropriate nSequence value. Of course, the replacing transaction must still follow all the other rules stated in BIP125 (notably regarding its fee). If enough nodes have this option enabled, this new policy would successfully protect users against the aforementioned attack because the multiparty transaction would be relayed by those nodes (provided it pays high enough fees).

Of course, the attacker could still set quite high fees to their conflicting transaction to force the other participants to pay high fees in the multiparty transaction. The difference is that the attacker used to be able to realize their attack even with a minimal fee and successfully prevent the multiparty transaction from propagating on the network. With mempoolfullrbf, the attack would be quite different in nature, closer to a fee-escalation scenario. Bob could easily increase the fees of the multiparty transaction (via CPFP) so that it respects the fees requirements of BIP125. Alice would then have to increase the fees of her own transaction, and so on. The attack is much more risky for Alice, as she faces the possibility of having her high-fees transaction beeing mined at any time, whereas she used to be quite safe in that regard because not signaling for replacement allowed her to disrupt the multiparty transaction even with a minimal fee.

The Merge

This modification has now been merged into Bitcoin Core without much controversy, as it doesn’t change the default behavior of Core. Indeed, the new configuration option is set to false by default, which means nodes will continue to only replace transactions that signal for replacement with an appropriate nSequence value. Only the nodes whom owner change the parameter’s value to true will start applying this new rule in their mempool. This also means that there are reasons to expect nothing will change regarding the aforementioned attack vector in the near future, as it is not perceived as a very direct threat. But the option will be there in the future for users who need it. In the meantime, it would also allow people and businesses that rely on 0-conf transactions to properly evaluate wether they need to adjust their procedures or not.

However, there is at least one shortcoming of this new mechanism in Core: it brings back some uncertainty. Right now, with BIP125 quite widely adopted amongst wallets and services, it is quite safe to assume that a transaction signaling against replacement will not be replaced4. If this becomes a per-node customizable behavior, things become a bit more blurry. This might be perceived as a push from Core to discourage the use of 0-conf transactions. It could also result in significant discrepencies between mempools, which is never a good thing.

TL;DR

A new customizable parameter has been added to Bitcoin Core. Node runners can now decide wether they want to allow the replacement of unconfirmed transactions in their mempool, even when said transactions do not signal for replacement. This new feature will give better protection against a certain kind of DoS attacks that can affect multiparty protocols built on top of Bitcoin. The compromise is that it might render 0-conf transactions a bit more unreliable, as well as introduce more discrepencies between mempools.

Ressources

You can (and should) dig deeper right to the source:

Additionnaly, you can give a listen to EDB-39 (in French 🇫🇷), where we discussed the subject.

Liked this article? Found a mistake? Wanna roast me for saying something dumb? Feel free to reach out on this Stacker News discussion to let me know! And if you really enjoyed your read, you can even send a few sats my way (click the big button). Thanks!

-

By “current” I mean the one actually running on most nodes. The “new” RBF policy proposed by Antoine Riard having been merged into Core, it could arguably be referred to as the “current” one, although it doesn’t run on any node yet, apart from testing purposes. Hence, for the sake of clarity, we will refer to the Opt-in RBF policy (BIP125) as being the current policy, while the mechanism proposed by Riard will be called the new policy. ↩︎

-

The nSequence is a number field attached to every input of a Bitcoin transaction (one nSequence per input, and nSequences can differ from one another), stored on 32 bits, which implies the maximum possible nSequence is 2^32, or 0xffffffff in hexadecimal representation. This choice was made to ensure backward compatibility, as setting nSequence to 0xffffffff - 1 was already used for timelocks. Therefore:

- a nSequence set to 0xffffffff clearly indicates that the transaction should not be replaced

- a nSequence set to 0xffffffff - 1 indicates the use of locktime and that a transaction should not be replaced

- any other nSequence indicates that the transaction can be replaced. ↩︎ -

The minimum relay fee is a per node policy. If a transaction pays a feerate (expressed in satoshis per vByte) below this thresold, then the node will not relay the transaction any further. Although each node is king it its realm, and users can set the minimum relay fee of their node to whatever they want, the default value is set to 1 sat/vByte, and I have personnaly never encountered a node with a different policy. It basically means that a transaction will not be relayed (at least, not efficiently) on the Bitcoin P2P network if its feerate is below 1 sat/vB. Howerver, we still see transactions paying below this feerate in blocks from time to time, either because they were broadcast directly to a miner, or because they are part of a greater package of transactions. ↩︎

-

EDIT (thanks to @cryptocoin on Stacker News for pointing this out): this is true for some use cases at least, like buying a small amount of good and services in a physical store (for example, when someone buys their weekly groceries with Bitcoin). Services that are particulary prone to being abused, such as exchanges or ATMs, can’t rely on such 0-conf assumptions, which is why they typically wait for a few confirmations. The uncertainty added by the new Full-RBF mechanism hence mostly affects in-person exchanges, which tend to increasingly use the Lightning Network in order to benefit from its instant settlement. ↩︎